Blog – The Calcutta Chromosome: Watching Byomkesh Bakshy in His City

Blog – The Calcutta Chromosome: Watching Byomkesh Bakshy in His City

THE STORY OF HOW I WATCHED THE DIBAKAR-DIRECTED CRIME THRILLERDETECTIVE BYOMKESH BAKSHY! IN THE CITY OF SO-CALLED JOY, MY FIRST HOME AND THE FICTIONAL BYOMKESH’S HUNTING GROUND

I will begin with a disclaimer – this is not a comment on either Dibakar Banerjee’s filmmaking nor on Sushant Singh Rajput’s acting (I loved both, despite some plotholes in the movie). It is merely the story of how I watched the Dibakar-directed crime thriller Detective Byomkesh Bakshy! in the City of so-called Joy, my first home and the fictional Byomkesh’s hunting ground.

I live now in Gurgaon and, indeed, have lived in and around Delhi for several years now – so many years, that I no longer trouble to make weekly visits to Chittaranjan Park, South Delhi’s Little Bengal, for assorted requirements ranging from Jharna ghee to phuchkas. Even less frequent now are visits to Kolkata and when I do return it is with a packed schedule of old haunts to renew acquaintance with. Mostly these haunts are food-related – Mocambo, Nizam’s and other favourite eateries – but on a just-concluded visit, I had an appointment with a hero of Bengal, private eye Byomkesh Bakshy, now rendered in a Bollywood version (although Dibakar’s crafting is the very opposite of ‘Bollywood’).

I had tickets to an afternoon show of the film on a Friday exactly a week after it had been in cinemas. By sheer happenstance, a visit to Kolkata coincided somewhat with the movie’s release and though it meant a delayed introduction to the Bollywood Byomkesh, it also meant I would be able to watch it with fellow Byomkesh fans, my family.

The cinema hall, a marvel of polished marble and plush carpeting to rival any Delhi multiplex, was the first revelation. There were several counters offering an almost dizzying selection of refreshments, popcorn being the most pedestrian of comestibles available. We bought nothing. At the now late and very much lamented theatres of my teen years – New Empire, Lighthouse, Globe, monuments to cinema in a vanished Calcutta now replaced by an often unfamiliar Kolkata – we would have fallen upon the unpretentious packets of popcorn that came in a solitary flavour and greasy crisps that you could buy from a single wooden counter or the man who came around in the interval with a plus-sized tray hanging from his neck. The popcorn and crisps came in one size only and if you wanted a larger helping, you bought two packets. In the swanky new theatre, we took our seats unfed. However, the bathrooms were magnificent, five-star.

In the two-and-a-half hours that followed, we sat eagerly through scenes of a city and a culture that we knew all too well, the difference in decades notwithstanding. Dibakar’s Byomkesh operates in 1943, but at several levels the Calcutta he lived in is unchanged. Tendrils of smoke impede vision and breathing in a fictionalised version of College Street’s Coffee House; rickshaws are ridden through winding bylanes; the obstacle course presented by the pavements of Bosepukur is navigated expertly; everywhere, there are ordinary Bengalis doing time-honoured Bengali things like walking home with a freshly-bought fish or rousing the rabble with revolutionary rhetoric.

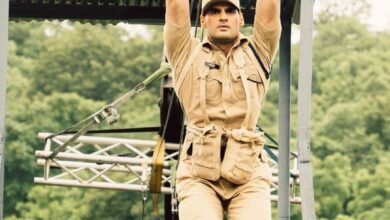

The second revelation was the Hindi-speaking Byomkesh. In a text message from Delhi, my husband expressed disbelief and mild shock that Bengalis had not only allowed a man with so North Indian a name to appropriate their beloved Byomkesh but also largely rubber-stamped his performance with their approval. Last week, Dibakar told news agencies that “from what we have gathered from (Kolkata), Sushant has really become Byomkesh for them.” This is because Sushant as Byomkesh is satisfactorily Bengali, even though he claims Munger in Bihar as his point of origin. He has ‘pet kharap‘ or indigestion for no good reason of narrative; the sight of blood makes him come over faint; he is alarmed by both female attention as well as physical violence. His eventual ally and assistant Ajit is able to fell him easily, in the very first scene. Later, Byomkesh cowers at the merest sign of another blow from Ajit. As a fight rages around him, he stands by irresolutely with a metaphorical wringing of hands and afterwards implores Ajit not to get into another fight. In the showdown sequence at the end, he alone of the ‘good guys’ is knocked down and stays down, spending the rest of the climax scene unconscious on the floor. Ajit is by far a hardier specimen of Bengali youth, ready with his fists and mindful of physical fitness.

After the movie ended, we the watchers spent a happy half hour discussing Dibakar’s alterations from the original stories, like Dr Anukul Guha who deals in cocaine in Saradindu Bandopadhyay’s books rather than heroin, and trying to recall if the book Byomkesh also had roots in Munger. That half hour would not have been available to me in a Gurgaon or Delhi cinema. Nor would the gleeful enumeration of Byomkesh’s Bengali traits have taken place.

We also discussed the possibility of a sequel and decided that Dibakar and Sushant – those who dared disturb the universe – have a very real duty to commit to a whole series of Byomkesh films, not just one sequel. For Bengal and the Bengalis.